Insecticide resistance

Project overview

Why this project?

Malaria is an important health issue in several West African countries, where it is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality. Across Africa, long-lasting insecticidal nets (LLINs) treated with pyrethroids and bendiocarb-based indoor residual spraying (IRS) are the key tools used for malaria control. However, populations of Anopheles species have developed resistance to insecticides used for mosquito control.

The aim

The aim of this two-year study has been to assess how well IRS and LLINs work in sites where Anopheles species have developed resistance to insecticides.

.jpg?sfvrsn=aa13be6f_0)

Objectives

Update data on insecticide-stance and determine resistance mechanism(s) in the three target countries in order to identify appropriate study sites where vectors harbour knock-down and metabolic-based resistance mechanisms.

The research sites

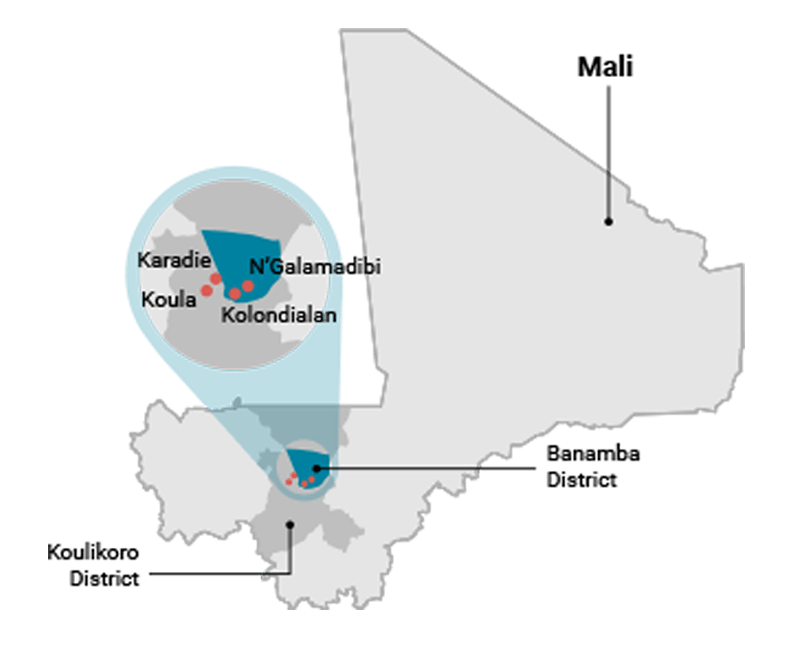

Mali

No site of susceptibility was observed in Mali; therefore, sites where indoor residual spraying (IRS) was utilised (using a class of insecticides to which the Anopheles gambiae s.l. population is susceptible) and sites where IRS was not utilized were considered:

- Koula and Karadiè in Koulikoro District (IRS and long-lasting insecticidal nets (LLINs) deployed)

- N’Galamadibi and Kolondialan in Banamba District (no IRS, only LLINs)

In Koulikoro and Banamba Districts, malaria transmission occurs mostly during the rainy season (June to October). An. gambiae s.l. is the predominant malaria vector in both study areas: > 98%.

Nigeria

The study sites in Nigeria were in Ikorodu District in south-western Nigeria, on the outskirts of Lagos:

- Imota

- Bayeku

- Oreta

- Igbokuta (control village)

Preliminary data were collected from 12 sites on vector species, insecticide resistance and type of resistance mechanism(s). Based on the initial analysis conducted, the above four sites were selected for the study.

The climate of this area is characteristic of the forest zone. The rainy season is from April to October and the dry season is from November to March. The area is usually flooded during the rainy season; larval aquatic habitats are abundant throughout the year.

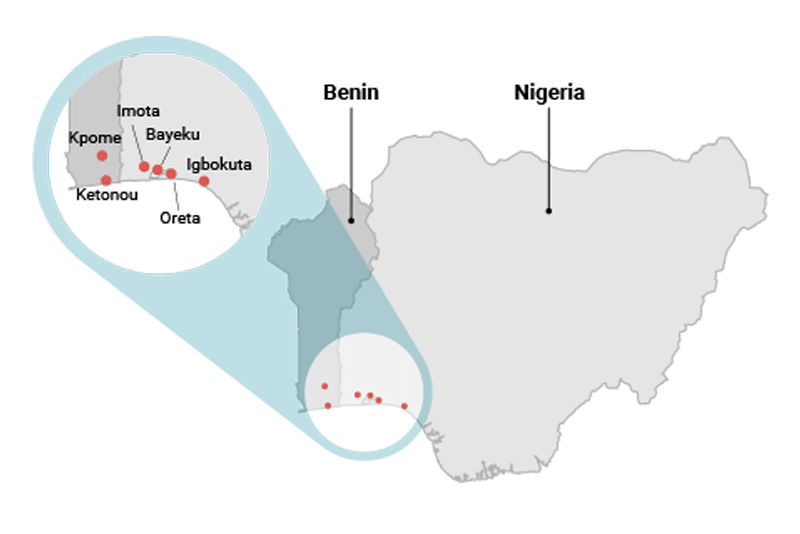

Benin

No site of Pyrethroid susceptibility was recorded in Benin; therefore, two sites with consistent differences in resistance levels were considered:

- Kpome, a site where Anopheles species are resistant to pyrethroids (13% mosquito mortality with Permethrin and 46% mortality with Deltamethrin); and

- Ketonou, a site where Anopheles species are less resistant to pyrethroids (27% mosquito mortality with Permethrin and 76% mortality with Deltamethrin).

Both localities are in the same agro-ecosystem.

Key findings

Key findings: Mali

- Malaria vectors in Mali showed widespread and increasing resistance to insecticides, especially pyrethroids; multiple resistance mechanisms were recorded in studied localities.

- The effect of resistance on the performance of long-lasting insecticidal nets (LLINs) was recorded; however, organophosphate-based indoor residual spraying (IRS) introduction in some study sites seemed to moderate the negative effect of the above-described resistance phenomenon. Vector populations remained susceptible to the organophosphate-based class of insecticide.

- A good insecticide resistance management and implementation plan should be developed.

- Education regarding the causes and risks of malaria and the usage of LLINs should be increased.

Key findings: Nigeria

- Anopheles gambiae s.s. was the main Anopheles species, constituting 80–100% of the Anopheles population in the different villages.

- LLIN coverage in Ikorodu was low, with the socio-anthropological data revealing that LLIN use was not common in the four villages. Less than 20% of households surveyed owned a net.

- LLIN coverage in the four villages was low prior to net distributions due to non-availability of LLINs in the market.

- Sleeping under LLINs greatly reduced the number of mosquito bites a person received.

- In areas where mosquitoes had metabolic resistance, net ineffectiveness was shown by mosquito bites received while sleeping under LLINs, and by the presence of live mosquitoes hanging onto LLINs.

"In Nigeria, less than 20% of households surveyed owned a net."

Key findings: Benin

- Mosquitoes (An. gambiae and An. funestus) from most surveyed sites were found to be resistant to the pyrethroid insecticides used as malaria vector control measures.

- The level of insecticide resistance varied from the north to the south of Benin, with higher resistance recorded in the south.

- In the two selected study sites, it was found that there was higher resistance to pyrethroids in Kpome than in Ketonou.

- Results from experimental huts and from households revealed that malaria transmission indices (entomological surveys) increased with the resistance levels of the mosquitoes.

- Although the number of malaria cases was almost similar in both localities, more severe malaria cases were recorded in Kpome, the locality with a higher resistance level.

Despite high net coverage (>75%) recorded in both study sites, malaria cases were still recorded in several households, which could have been due to:

- The high resistance level of mosquitoes to insecticides (multiple insecticide resistance mechanisms, both metabolic and target mutations);

- The reduction of insecticide residues in net fibres as a result of net washing practices; and

- The poor sleeping behaviours of net users, as some net users' hands and limbs were in contact with nets while they were sleeping.

Research components

Parasito-clinical characterization of sites

Methodology

In Mali, Nigeria and Benin, data on malaria prevalence in the study sites was collected through surveys and, in some cases, from local community health centres. The surveys included demographic data, such as age and gender, in order to understand which groups were most affected by malaria. Data of malaria cases was cross-analysed against net use, net types, the physical quality of nets, insecticide residues on nets, and the sleeping behaviours of net users.

Findings: Mali

- Cross-sectional surveys reported lower values in all parasitological indices, including Plasmodium falciparum prevalence, gametocyte rate and incidence in the indoor residual spraying (IRS) sites compared to non-IRS sites.

- The expected seasonal peak in the parasitological indices at the end of the transmission season was suppressed in sites with IRS, while it was apparent in sites without IRS.

- The incidence rate was 2.5 times higher in non-IRS sites (6.8 episodes for 100 person-month) than in IRS sites (2.7 for 100 person-month).

- Children living in IRS sites were more likely to be protected against malaria than those in non-IRS sites.

"In Mali, the expected seasonal peak in the parasitological indices at the end of the transmission season was suppressed in IRS sites, while it was apparent in sites without IRS."

Findings: Nigeria

- Baseline malaria prevalence surveys showed a similarity in malaria prevalence across the three resistance villages - Imota, Bayeku, and Oreta.

- The control village, Igbokuta, had a prevalence of 14.9% to 16.8% in children aged 1 to 10 years and 23.2% to 27.8% in people aged 11 to 60 years.

Findings: Benin

- Recorded parasito-clinical results revealed that more cases of severe malaria were recorded in Kpome (6.92%) than Ketonou (0%).

- In both localities, communities were protected with treated nets (>75% in both); but mosquitoes from Kpome were more resistant (through multi-resistance mechanisms) than those from Ketonou.

- Despite the high net coverage recorded in both study sites, several malaria cases were recorded in households, which could have been due to the high resistance level of mosquitoes to insecticides (multiple insecticide resistance).

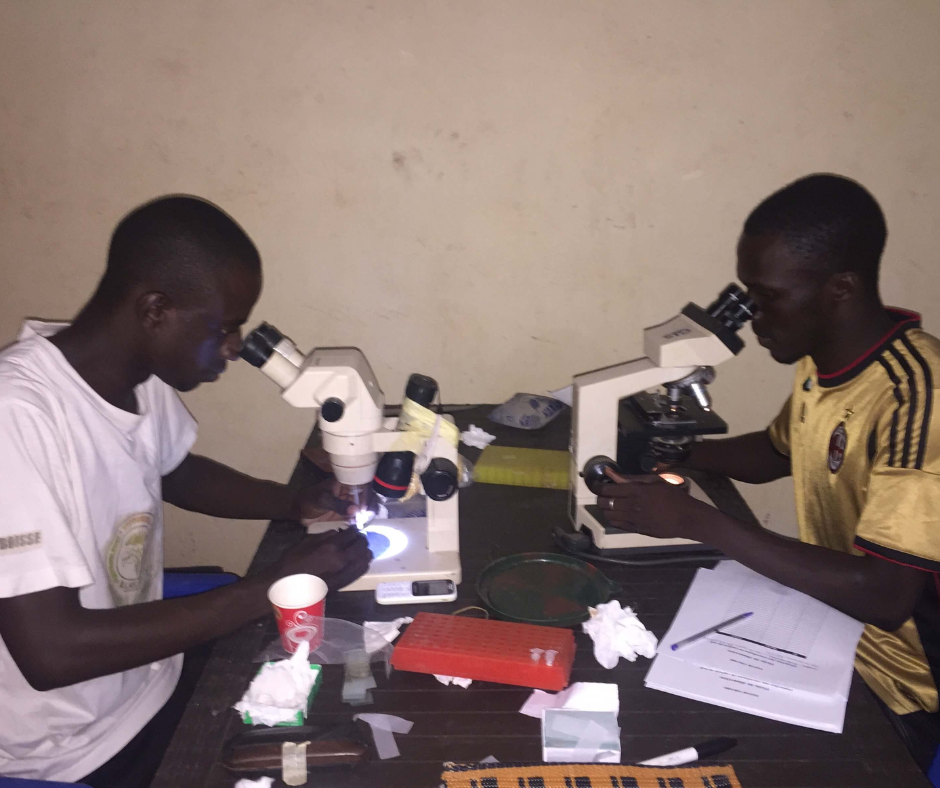

Entomological component

Methodology

In Mali, Benin and Nigeria, mosquitoes were collected and analysed to determine which vector species were present and whether they were infected with the malaria parasite. Research conducted included:

- Mosquito collection in human dwellings using pryrethrum spray catches (PSC) and WT methods;

- Phenotypic and genotypic profiling of malaria vectors in selected sites.

Additional activities were also conducted in some study sites, such as:

- Experimental hut trials of the effect of developed insecticide resistance on entomological indices of malaria transmission; and

- High performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis of insecticide residues in net fibers (a laboratory technique) during the study period.

Findings: Mali

- An. gambiae s.l. was the predominant malaria vector present in the mosquito catches. Very few An. funestus were reported in some localities.

- The resistance level had recently increased across localities, including in the presumed susceptible locality. Thus, no site susceptible to pyrethroids was found.

- Vector populations in all sites were fully susceptible to the organophosphates (pyrimiphos-methyl) currently used for IRS in Mali.

- Except for human blood index, all entomological transmission indices (including vector density per house, biting and infection rates) were lower in indoor residual spraying (IRS) sites compared to those without IRS.

- Transmission as measured by entomological inoculation rate (EIR) was undetectable in IRS sites, while it was still high in areas without IRS. This demonstrates a recurring issue: limited access to LLINs and no clear policy to replace worn or damaged nets.

- It was unknown when and how often IRS was carried out.

"In Mali, it was unknown when and how often IRS was carried out."

Findings: Nigeria

- Baseline entomological data revealed Anopheles gambiae s.s. as the major Anopheles species in the four villages, representing more than 90% of the Anopheles population at each site.

- Mosquito indoor density was similar at the four sites, ranging between nine and 13 mosquitoes per room per day.

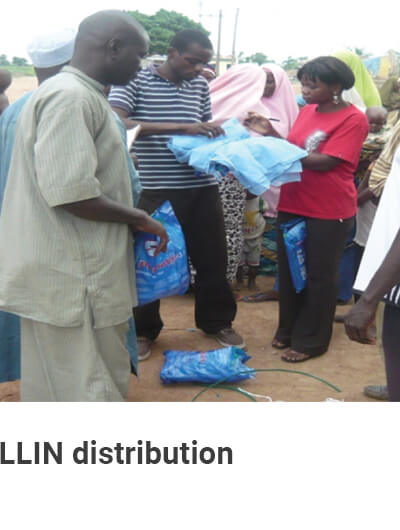

- LLINs were distributed to the inhabitants of the four villages according to the Nigerian national guideline of two LLINs per household.

Findings: Benin

- Entomological results generated from activities conducted in Benin revealed that mosquitoes (An. gambiae and An. funestus) from most surveyed sites were found resistant to pyrethroid insecticides used in malaria vector control measures in Benin (multiple insecticide resistance, both metabolic and target site mutations).

- The level and intensity of resistance varied from the north to the south, with higher resistance recorded in the south.

- Data from experimental hut trials conducted at this site revealed higher transmission risk with released resistant mosquitoes (compared to susceptible mosquitoes) for individuals sleeping in huts and protected by treated nets (LLINs).

- In the two selected study sites, it was found that there was higher resistance to pyrethroids in Kpome than in Ketonou.

- Results from experimental huts and from households revealed that malaria transmission indices (entomological surveys) were higher as the resistance levels of mosquitoes increased.

- Low presence of insecticide residues in LLINs used by identified malaria patients was recorded, in comparison to those without malaria, whose nets had more insecticides.

Sociological component

Methodology

Interviews and focus group discussions were held with risk groups to find out more about:

- Net coverage in the selected study sites

- Net use and sleeping patterns

- Behaviours and practices likely to affect the efficacy of LLINs when used in target study sites

Findings: Mali

- LLIN utilisation varied from village to village, with the lowest rate in the non-IRS sites (60 to 70%) and the highest in IRS sites (75 to 85%).

- The main reasons for using the LLINs were protection against mosquito bites and malaria.

- Reasons for not using the LLINs included to avoid tearing, space issue in the room, heat, and the absence of mosquitoes.

"In Mali, LLIN use varied from village to village, with the lowest rate in the non-IRS sites (60 to 70%) and the highest in IRS sites (75 to 85%)."

Findings: Nigeria

- Respondents highly appreciated the LLINs provided, with more than 90% in both the resistance and control villages confirming that:

- They experienced a great reduction in mosquito bites when sleeping under LLINs;

- There were dead mosquitoes on the floor, bed and mats when using LLINs; and

- They were willing to pay to continue using the LLINs.

- However, in Bayeku and Imota, 5% and 2.2% of the nets distributed, respectively, could not be found three months after distribution. The reasons for halted usage included:

- Individuals were still being bitten by mosquitoes while sleeping under LLINs;

- Mosquitoes were seen hanging on the LLINS;

- Skin irritation was believed to be due to body contact with LLINs; and

- People felt that it was hotter when sleeping under LLINs.

Findings: Benin

- Most people did not erect their mosquito nets properly.

- In some cases, bed nets were permanently erected, promoting mosquito entry into the nets even before going to bed in the evening.

- People spent a lot of time outside in the evening (while mosquitoes were active) before going to bed.

- The size of the nets did not match the sizes of the beds.

- Most participants agreed that the use of LLINs was the only effective means against mosquito exposure; and increased demand for bed nets was observed in the community. LLINs were heavily used in households, especially at night, due to the high biting rate of mosquitoes.

- In both localities, communities were protected with treated nets (net coverage higher than 75%); but mosquitoes from Kpome were more resistant (multi-resistance mechanisms) than those from Ketonou.

- Although LLINs offered physical protection, the presence of multi-resistance affected their efficacy. Data from this research project also revealed that this protection further dropped when the level of insecticide in net fibres diminished and when net users had their hands or limbs in contact with the net when sleeping, as recorded in both study sites.

Research uptake

Research uptake objectives

This study will contribute to improving malaria vector control strategies through:

- Appropriate selection of insecticides for IRS and LLINs;

- Improving information for increasing net use; and

- Developing sensitisation messages, for the purpose of good practise, such as a sensitisation video developed on the proper use of LLINs at the community level.

- Overall, this knowledge about IRS and LLINs' performance in areas where malaria vectors have developed different mechanisms of resistance will enable better resistance management strategies to be applied in local areas.

Sharing Results

Results will be shared through the following channels:

- A regional knowledge database will be created with resources about the impact of the different insecticide mechanisms on the performance of LLINs and IRS in different ecological zones;

- Leaflets and posters will be shared with local communities; and

- Meetings will be held with local and national government officials.

Key Audiences

The key audiences for this study are therefore:

- ERC Secretariat

- Health service providers (direct users of research outcomes) (e.g. NMCP, health clinic personnel, NGOs)

- IVM focal points

- Programme managers (in government)

- Implementation partners working with communities at local level/local mosquito control agencies

- Municipal health authorities

- Ministries of Health

"A regional knowledge database will be created with resources about the impact of the different insecticide mechanisms on the performance of LLINs and IRS in different ecological zones."

Publications and other resources

Video

The Principal Investigator, Dr Nafomon Sogoba, was interviewed at the workshop on Residual Malaria held in Iquitos, Peru in 2019. In this video, he describes the aim and key findings from his project.

Summary booklets

These booklets provide an overview of the projects aims, methods and key findings. It also includes some suggested recommendations for how to address ongoing malaria transmission in the local context. These documents are targeted toward decision makers and other authorities in malaria control in South-East Asia. View the booklet for Mali and Nigeria here and here

Publications

Keïta M, Kané F, Thiero O, Traoré B, Zeukeng F, Sodio AB, Traoré SF, Djouaka R, Doumbia S, Sogoba N. (2020). Acetylcholinesterase (ace-1R) target site mutation G119S and resistance to carbamates in Anopheles gambiae (sensu lato) populations from Mali. Parasit Vectors.13(1):283. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32503614/

Kané F, Keïta M, Traoré B, Diawara SI, Bane S, Diarra S, Sogoba N, Doumbia S.(2020). Performance of IRS on malaria prevalence and incidence using pirimiphos-methyl in the context of pyrethroid resistance in Koulikoro region, Mali. Malar J.19(1):286. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32787938/

Keïta M, Sogoba N, Kané F, Traoré B, Zeukeng F, Coulibaly B, Sodio AB, Traoré SF, Djouaka R, Doumbia S. (2021) Multiple Resistance Mechanisms to Pyrethroids Insecticides in Anopheles gambiae sensu lato Population From Mali, West Africa. J Infect Dis. 223(Supplement_2):S81-S90. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33906223/

Keïta M, Sogoba N, Traoré B, Kané F, Coulibaly B, Traoré SF, Doumbia S. (2021) Performance of pirimiphos-methyl based Indoor Residual Spraying on entomological parameters of malaria transmission in the pyrethroid resistance region of Koulikoro, Mali. Acta Trop.216:105820. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33400915/

Gallery

Collaborating partners

Donor

This work is financially and technically supported by TDR, the Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases. Technical support is also provided by the World Health Organization Global Malaria Programme.

Partners

- Malaria Research and Training Center, University of Sciences, Techniques and Technologies of Bamako, FMOS.

- The International Institute of Tropical Agriculture (IITA), Cotonou, Benin

- Centre de Recherche Entomologique de Cotonou (CREC), Cotonou, Benin

- Country National Malaria Control Program (CNMCP), Ministry of Health, Benin

- Ministry of Health, Cotonou-Benin / University of Abomey Calavi (UAC-Benin)

- Nigerian Institute of Medical Research, Yaba, Lagos, Nigeria

Collaborators

- Vector Group, Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, Liverpool, UK

- University of Witwaterstrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

- Biostatics Unit, Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute, Basel, Switzerland

Contact details

Principal Investigator: Dr Nafomon Sogoba

Malaria Research and Training Center, Faculté de Médecine et d’Odontostomatologie (FMOS), Bamako, Mali

Address: BP 1805 Point G Bamako, Mali

Tel (Office): +223-20225277

Mobile: +223-66985887

Email: nafomon@icermali.org