TDR has a rich history of encouraging and supporting community participation. A recent study in India used approaches such as witness seminars to help identify key aspects of community engagement. The study’s findings will add to the growing body of knowledge in this area.

“The importance of engaging communities in research can be easily seen when engagement is lacking” says Michael Mihut, who heads the Programme Innovation and Management unit at TDR. Poor community engagement can lead to communities rejecting public health interventions, thus negating the immense time, effort and money invested in research and development.

“In order to identify which engagement practices could be scaled up and disseminated, it is also important to identify good practices from real-life settings where community engagement has taken place,” adds Abraham Aseffa, who heads the Research for Implementation unit at TDR.

Identifying best practices in engaging communities

In 2021 a joint call for proposals went out from TDR, SIHI (the Social Innovation in Health Initiative) and WHO regional offices to identify good practices in engaging communities in research and social innovation with an intersectional gender perspective in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).

Although studies with active participation of communities in Africa, Asia and Latin America have been supported previously, this was the first call to directly focus on community engagement and, importantly, on cataloguing, appreciating and evaluating the community engagement strategies employed and approaches adopted.

The 10 projects selected, each of which received an award of US$ 30,000, explore a wide range of community engagement activities. Project Principal Investigators (PIs) of the selected projects were based in a number of LMICs (Cameroon, Ethiopia, Ghana, Guatemala, India, the Islamic Republic of Iran, Kazakhstan, Malaysia, Philippines and Uganda). The lessons from these best practice studies will be compiled, analysed and then disseminated in collaboration with the study teams.

Of the ten community engagement projects recently supported, one project looked at the challenges of community engagement in India relating to tuberculosis (TB).

Exploring community engagement in India

TB continues to be a public health concern around the world, with millions affected by it. It is especially important in India, said to be one of the eight countries which together account for two‐thirds of all new cases worldwide.

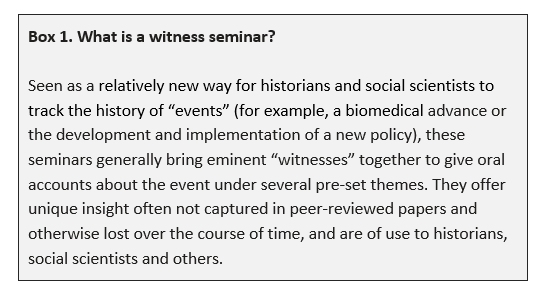

“Our project had two key strands”, says project PI Dr Sunita Bandewar. “Strand A involved witness seminars [see Box 1] while strand B involved qualitative research. The two witness seminars

we organized, building on the characteristics and strengths of witness seminars, were aimed at better understanding how the involvement of (and engagement with) communities was conceptualized and operationalized.”

“Our project had two key strands”, says project PI Dr Sunita Bandewar. “Strand A involved witness seminars [see Box 1] while strand B involved qualitative research. The two witness seminars

we organized, building on the characteristics and strengths of witness seminars, were aimed at better understanding how the involvement of (and engagement with) communities was conceptualized and operationalized.”

Sunita, who is Secretary General of the Forum for Medical Ethics Society (FMES) and Director of the Health, Ethics, and Law Institute for Training, Research and Advocacy (the HEaL Institute), which hosted the project, added that through these projects the researchers hope to “better understand the current practices in engaging communities in research” and “to contribute to the scholarship in this relatively under-explored area in India, especially with reference to implementation research.”

Strand A: Witness seminars: Producing witness seminars requires extensive preparation and management, including:

- brainstorming ideas and identifying themes

- shortlisting witnesses/speakers

- organizing and hosting the seminars (in person or online)

- transcribing proceedings, seeking approvals from speakers, and producing reports

- disseminating outputs

- recognise diverse perceptions of the term “community engagement”, requiring nuanced approaches to designing and implementing community engagement strategies.

The two witness seminars in strand A brought together 21 witnesses from diverse backgrounds to give their unique perspectives. The first seminar sought perspectives from those involved in the development and implementation of India’s TB programme, while the second focused on the perspectives of those affected by TB (patients/survivors) or those who have worked with communities (advocates and activists).

These witness accounts highlight challenges and opportunities (both past and present) and other issues relating to engaging the community/patients with India’s TB programme.

Selected key issues raised during the witness seminars include the need to:

- engage marginalized communities (e.g. tribal populations, transgender persons, migrant workers and people who take drugs) and appreciate structural and situational vulnerabilities;

- uphold patients’ dignity and autonomy and avert patient–provider power asymmetry and patient ‘infantilization’;

- keep counselling central to patient care (versus generalized/impersonal information);

- have robust community engagement strategies to address the stigma and discrimination that TB patients and/or their families are subjected to both in healthcare system and in communities, and to avert the criminalization of TB patients;

- ensure that the health administration views patients, their families, and communities as stakeholders and champions in TB programmes;

Below are some examples of statements made by witnesses during the seminars that emphasize the importance of engaging patients and communities:

- “Community engagement should be non‐negotiable. It should be a component that is as important as every other aspect of TB programme whether it is about ending TB or addressing TB.”

- “The bottom line is that when we don't include people who are affected the most in such processes, we end up with ineffective policies and top‐down approaches.”

- “Communities shouldn’t be dismissed, infantilised or made to feel helpless.”

- “Patient centric means…what matters to the patient, and not what is the matter with the patient.”

Outputs from the witness seminars were shared with relevant national and international networks, entities and influencers (e.g. through a virtual e-release meeting) and disseminated more widely through social media.

Strand B: Qualitative research: Known as Eco-researchTM (Engagement of Communities in research in Tuberculosis and Mental Health), this collaborative research initiative aimed to catalogue key community engagement practices embedded in two implementation research public health projects involving disadvantaged (rural/indigenous) communities in India: RATIONS (addressing TB) and TeaLeaf (addressing mental health).

For the study, teams of researchers sought the views of around 90 community stakeholders (previously identified through systematic stakeholder mapping) during 50-or-so interactions comprising of in-depth interviews, joint

in-depth interviews, and focus group discussions. The shape of these interactions and focus of the conversation was guided by prior thematic mapping. Given pandemic-related constraints, these interactions were virtual as well as in-person in the field

at the two sites. Audio recordings made during these interactions were later transcribed and translated.

For the study, teams of researchers sought the views of around 90 community stakeholders (previously identified through systematic stakeholder mapping) during 50-or-so interactions comprising of in-depth interviews, joint

in-depth interviews, and focus group discussions. The shape of these interactions and focus of the conversation was guided by prior thematic mapping. Given pandemic-related constraints, these interactions were virtual as well as in-person in the field

at the two sites. Audio recordings made during these interactions were later transcribed and translated.

A selection of study findings

From across the two projects, the data suggest that “soft facets” – such as trust earned by research team members from intervention participants – were valuable for community engagement, especially when dedicated resources for community engagement (finances, time, niche expertise) are limited.

Several field investigators also experienced a sense of satisfaction in their work when they witnessed so-called hopeless cases (study participants) turning into inspiring stories of survival. This further motivated them

to take on more challenging situations in the field.

Several field investigators also experienced a sense of satisfaction in their work when they witnessed so-called hopeless cases (study participants) turning into inspiring stories of survival. This further motivated them

to take on more challenging situations in the field.

Two quotes are given below, for example.

[Field investigator] “We ourselves coordinated with the TB Programme staff at field sites ... It lent us credibility as reliable and knowledgeable RATIONS project team members. It helped us build trust and confidence amongst the staff.”

[Patient’s story shared by field investigator] “I had received very bad treatment in the hospital. Their staff used to behave badly with me, they always kept physical distance from me while talking and doing medical check-up [sic], and used to throw medicines at me instead of handing them over to me ... But the way you people talked to me, counselled me about adverse impact of drinking, and that you touched me, shook my hands, made a difference.”

“It was an incredible experience to be on the ground with two seminal implementation projects in India involving marginalized communities,”

said Sunita. She added: “One of the most striking features in both these projects is that the researchers have about a decade-long engagement with the respective health issues, and a close relationship with communities and stakeholders. This

reality underscores that community engagement can be viewed differently from the conventional view that engagement is restricted to the lifespan of a project. Insights from the two projects highlight the central role that funders and research ethics

boards have in enabling meaningful engagement in implementation science in LMICs. I would hope that bodies such as TDR continue to support such somewhat long-term projects in countries like India.”

“It was an incredible experience to be on the ground with two seminal implementation projects in India involving marginalized communities,”

said Sunita. She added: “One of the most striking features in both these projects is that the researchers have about a decade-long engagement with the respective health issues, and a close relationship with communities and stakeholders. This

reality underscores that community engagement can be viewed differently from the conventional view that engagement is restricted to the lifespan of a project. Insights from the two projects highlight the central role that funders and research ethics

boards have in enabling meaningful engagement in implementation science in LMICs. I would hope that bodies such as TDR continue to support such somewhat long-term projects in countries like India.”

The findings from the study are currently being analysed and manuscripts prepared for publication, one each for the two study sites.