A collaborative study between SIHI/TDR, UNICEF and UNDP on the role of the private sector in healthcare delivery in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) has just been completed in United Republic of Tanzania and Ghana and provides insights into how private sector engagement and interactions could be enhanced in order to improve quality of healthcare for women and children.

Back in 2020 the Executive Director of UNICEF, Henrietta H Fore, and the Administrator of UNDP, Achim Steiner, launched “The Big Think Challenge”. Their aim was to identify innovative solutions that accelerate progress to meet the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). A collaboration between UNICEF/UNDP and the Social Innovation for Health Initiative (SIHI) Uganda Hub received second prize; SIHI is a global network established under TDR leadership.

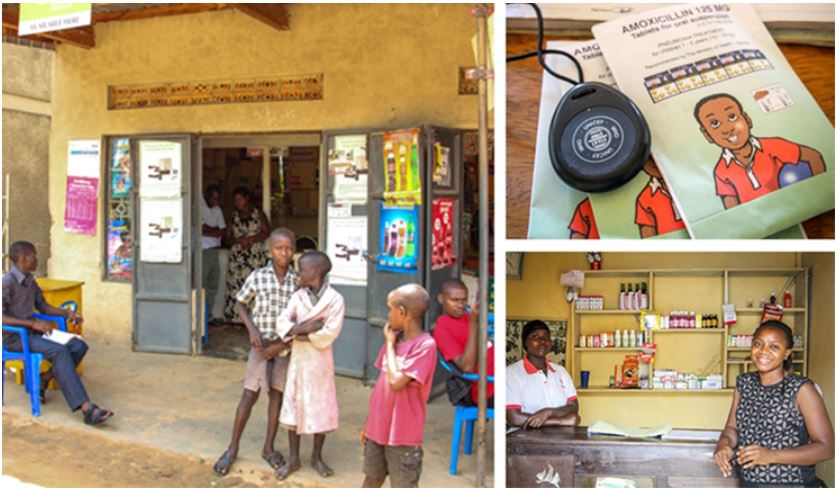

The SIHI/TDR, UNDP and UNICEF collaboration for the Big Think challenge has its foundation in the success of introducing the WHO/UNICEF-supported integrated Community Case Management (iCCM) strategy to address major causes of child mortality including, malaria, pneumonia and diarrhoea to private drug shops in Uganda led by Phyllis Awor (see later section on early work with the private sector).

For the Big Think project, the SIHI team and UNICEF’s research managers worked together to determine the best way to use the US$ 100,000 award to understand how to work with private providers in LMICs at the primary healthcare level, and thereby improve universal health coverage (UHC). The project team has just concluded a systematic scoping literature review and two country assessments – one in Tanzania (East Africa) and the other in Ghana (West Africa) on private provider engagement in primary healthcare for women and children.

A systematic scoping literature review

The systematic review looked at both published and grey literature from multiple countries over the last 20 years (2000–2021). There were some clear conclusions from the review. For example, it was apparent that the private sector plays different roles in different settings/countries and therefore no single standard intervention or approach will work in all contexts. The literature also suggested that while the private sector is the dominant provider of outpatient care, it is less so for inpatient care.

The review findings also led to the conclusion that different strategies for engagement with private sector health providers are needed at macro/national level (where policy development occurs), meso (regional and district) level, and micro (individual provider) level. For example, at macro and meso level, the private sector needs to be involved in the development of policies that affects it (including development and ownership of contracting arrangements). At the micro level, regulatory and financing tools as well as direct quality improvement interventions could be used to influence provider behaviour/service quality.

Country assessments in the United Republic of Tanzania and Ghana

The country assessments in the United Republic of Tanzania and Ghana that were also carried out as part of the study involved a large number of in-depth interviews with key stakeholders.

Examples of some of the findings from the assessments in the United Republic of Tanzania and Ghana

United Republic of Tanzania

- Private sector facilities account for 30% of the total facilities. A large portion of private sector facilities are run by NGOs or faith-based organizations (FBOs), contributing to 22% of all the health care provision.

- FBO facilities are often in remote areas where public facilities are not available.

- About half of all training institutions are privately owned.

- 12% of women give birth at private health facilities.

Ghana

- The private sector contributes to 42% of all health service delivery.

- In relation to child health: seeking care from the public sector is higher than from the private sector, although use of the private sector is still significant (30% of the poorest and 49% of the wealthiest child caregivers use the private sector).

- 10% of women give birth at private health facilities.

The country assessments led the researchers to make recommendations to the two governments, to regulatory bodies, and to UNICEF and other UN agencies.

For example, for the United Republic of Tanzania researchers recommend that:

- the government review and update private provider accreditation/licensing requirements in collaboration with providers;

- regulatory bodies should establish a “one-stop shop” to streamline registration/regulation;

- UNICEF/UN agencies should revive support for reproductive and child health and expand coverage for neonatal health care through private sector engagement.

Meanwhile, for Ghana the researchers recommend that:

- the government update the private health sector policy with guidelines on the engagement of private health providers, and provide incentive and support for private health providers to establish facilities in rural and remote areas;

- that regulatory bodies intensify their monitoring activities through regular visits to private health facilities and that they strengthen private health provider associations.

Study findings were disseminated to and discussed with key target audiences, including ministries of health and their implementing partners. This dissemination has now been completed in both the United Republic of Tanzania and Ghana. Publications on the work have been prepared and are undergoing peer review.

Alluding to the how the research was carried out, Robert Scherpbier, who co-coordinated the project for UNICEF together with Anne Detjen, stated "this study, the result of collaborative efforts [see acknowledgements], demonstrates the importance of private provider engagement, especially in helping the most underserved access outpatient care".

Early work with the private sector: drug shops

“You can't just hide your head in the sand and think that by having a policy that says ‘no antibiotics at drug shops’ that the policy is implemented,” says Phyllis Awor, who heads the SIHI Uganda hub. Her ground-breaking research in Uganda from 2012 explains why she believes health policies and implementation programmes need to be realistic. Her ongoing work since then has explored the role of the private sector and highlights why the sector should not be overlooked – especially in LMICs. Here we refer to the work that set Phyllis off on her remarkable career trajectory.

Back in 2012 Phyllis was a physician at the start of her research career. Now, just 10 years later, she is sought out by international agencies for her expertise. It was while she was doing her PhD under the University of Bergen in Norway that Phyllis’s work with the private sector in Africa really started. The research group that she was part of was looking into how the WHO/UNICEF supported Integrated Management of Childhood Illness (IMCI) strategy for malaria, pneumonia and diarrhoea could improve quality of care for children by training public sector community health workers. However, no matter how much training was given, there seemed to be a maximum to the benefit attained. What was happening was that rural families with unwell children were turning to private sector drug shops as their first port of call to seek care. “Drug shops are the main source of care for children in low-income settings,” says Phyllis. “Around 40- 70% of care for common febrile illnesses happens at the level of these drug shops.”

Phyllis’s group had little expertise on the private sector, so a colleague turned to her and asked something that would transform her career: Would she be able to look at drug shops?

At the time the standards of care at drug shops were poor – on appropriateness of care, on use of clinical guidelines and in the medicines provided.

As part of her research, Phyllis introduced the iCCM strategy used for public sector community health workers to the level of these private sector shops by training drug store staff. Within a short time, her work was showing interesting results. “We found that on comparing intervention drug shops with control drug shops, there was an exceptional improvement in the quality of care e.g. the use of diagnostics and appropriate

treatments for malaria improved four-fold, while that for children with diarrhoea improved 13-fold.” Interestingly, Phyllis points out, the drug shop staff were keen to receive this training as it meant that the quality of care they gave was improved.

The Drug Shop Integrated Care was selected in 2015 as one of the 23 research case studies conducted by SIHI. Phyllis’s work led to an important change in policy in Uganda which now integrates drug shops and private health providers in iCCM interventions.

Reflecting on this foundational work, and following the latest Big Think study, Phyllis Awor stated that “governments and partners need to work more closely with private health providers. Our work [in the Big Think study] provides a framework and key recommendations for this.”

Acknowledgements

It is impossible to acknowledge all those involved with the Big Think project. Below is a list of some of the key organizations and individuals.

- UNICEF: Anne Detjen; Robert Scherpbier (UNICEF representative on TDR’s Joint Coordinating Board)

- UNDP: Belynda Amankwa; Leslie Ong

- TDR: Abraham Assefa; Beatrice Halpaap

- SIHI Uganda: Phyllis Awor

- SIHI Ghana: Phyllis Dako-Gyeke, Philip Tabong

- Consultants: Samuel Chatio (Ghana), Wema Kamuzora (the United Republic of Tanzania)

- Country colleagues:

UNICEF Tanzania – Ulrika Baker

UNICEF Ghana – Mrunal Shetye