For as long as he can remember, Bill Brieger has been interested in Africa. He got his first chance in 1972 to go there as a 22-year-old, covering thousands of miles visiting project sites in Sudan, Ethiopia, Kenya, Madagascar, Ghana, Cameroon, Nigeria,

Togo for the United Nation’s global Freedom from Hunger campaign.

Bill Brieger | Four years later, Brieger went back, this time with a newly minted master’s in public health (MPH) from the University of North Carolina. A Nigerian friend from his MPH programme had returned to Nigeria to help the University of Ibadan launch its own MPH programme in health education, the first in Africa, with support from the World Health Organization and the Nigerian federal government. Brieger decided to pay him a visit, and arrived to find that Ibadan was hiring. “It was supposed to be a short trip,” he recalls. “And then they offered me a contract.” |

Thus began the young scientist’s 26-year stint with the African Regional Health Education Center (ARHEC). There, Brieger built a career around the study of health and health care from the community perspective. The author of more than 140 scientific

publications, he’s earned international renown for his research on preventive, illness and sick role behaviours as well as on the design and delivery of community-based primary health services for endemic tropical diseases, primarily malaria,

Guinea worm disease, and onchocerciasis (also known as river blindness).

A pioneer of community-directed interventions

“Guinea worm was the first thing I got into,” he says, jokingly adding, “fortunately it didn’t get into me.” Inspired by the 1978 Alma Ata Declaration on Primary Health Care, Brieger and colleagues at Ibadan worked to extend primary health care to remote rural communities in surrounding Oyo State by training volunteer village health workers. Guinea worm was a common problem there, he says, so care and prevention services for the parasitic disease were integrated into the training curriculum, including lessons on how to record results.

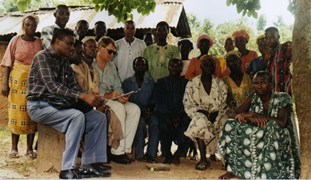

1998 community assessment in Elesifun, Nigeria Provided courtesy Bill Brieger | The same year Brieger arrived at Ibadan, Dr Ade Lucas, head of the Department of Preventive and Social Medicine, was leaving for Geneva to take over as TDR Director, a position he would hold for the next decade. “Professor Lucas always kept our staff informed of grants,” he remembers. When a three-year TDR grant to train community health workers (CHWs) on managing febrile illnesses and diarrhoeal diseases was announced, a former MPH classmate was asked to pull together a team and a proposal, and Brieger helped. |

“We applied, and we got it,” and it was that early support, he says, that really kick-started his scientific career, allowing for the scale up of the community-directed interventions (CDI) already underway. “That one project went on

to generate at least fifty publications by Ibadan faculty in follow-up research,” he recalls. “That helps in the academic setting, of course, but it also gives you clues about where to go next.

Just one project went on to generate at least fifty publications by Ibadan faculty in follow-up research.

Indeed, with the TDR grant, Brieger and colleagues were able to test the concepts of community-based primary health care, a forerunner of CDI, among hundreds of villages in the surrounding Oyo state. “We were training people to use what was available,” he says, noting that their objective was to make the training less didactic and more participatory. “We tried to model the kind of health education activities the CHWs would use, like songs and proverbs and role playing.”

In 1999 Brieger was invited to serve on TDR’s Task Force on Community-Directed Treatment of Lymphatic Filariasis and Onchocerciasis, which advised the African Programme for Onchocerciasis Control (APOC). A member of a team of independent scientists, he developed instruments to monitor the implementation of community-directed treatment with ivermectin in APOC countries, and headed up the monitoring team in Uganda. Using community-directed distributors selected by the community, APOC managed to scale up ivermectin distribution from 1.5 million in 1995 to more than 75 million people in 2010.

That was the start of a decade of providing technical assistance to a wide variety of TDR committees and task forces, and the evolution of this exciting new approach.

Community and system approaches for malaria control

| APOC’s success sparked widespread interest in applying the CDI strategy to tackle other diseases, and Brieger soon turned his attention to malaria. His research around the disease, much of it supported by TDR, included an assessment

of the acceptability of pre-packaged antimalarial drugs; treatment behaviour in urban settings; the role of patent medicine vendors and ways to improve their practice; and community and cultural perceptions of malaria as a basis for village

health worker training and health education. He went on to advise networks and organizations like the Roll Back Malaria Partnership and the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), providing technical assistance and helping to develop national guidelines in Nigeria on malaria in pregnancy. |  2008 community health education on malaria in pregnancy Provided courtesy Bill Brieger |

A megaphone for neglected tropical diseases

Brieger has long been a vocal commentator on issues relating to the control of tropical diseases, mainly from a health systems perspective. His primary vehicle is the widely-followed blog (www.malariamatters.org) he first launched in 2006 while serving as malaria adviser to the VOICES malaria advocacy project in The Johns Hopkins University’s Center for Communication Programs. The name has been changed to Tropical Health Matters, and Brieger frequently writes about the control of onchocerciasis, lymphatic filariasis, Ebola virus disease, and other neglected tropical diseases. He also reviews malaria research for the magazine Africa Health.

He is also a prolific tweeter (follow him at @bbbrieger), making him something of a rarity among public health professionals. And Brieger continues to teach, at Johns Hopkins University and through online courses on Coursera. A former student recounted admiringly in the JHSPH Magazine that “Professor Brieger was actually out in the field in Africa doing his work” while the course was going on. “It was pretty neat to hear from someone who was working on the issues he was talking about.”

For more information, contact:

Makiko Kitamura

TDR Communications Officer

Telephone: +41 22 791 2926

email: kitamuram@who.int