This project is a follow up from an earlier collaboration made possible by the TDR IDRC Research Initiative on VBDs and Climate Change, with research projects in South Africa, Kenya, Tanzania and Cote d'Ivoire. The collaboration was aimed at reducing population health vulnerabilities and increasing resilience against vector borne diseases (VBD) risks under climate change conditions in Africa. The South African project branded as MABISA (Malaria and Bilharzia in Southern Africa), was implemented in Botswana, Zimbabwe and South Africa. In addressing the overall theme of the TDR IDRC Research Initiative, the MABISA project identified research gaps that impeded control, prevention and elimination of malaria and schistosomiasis in the 3 countries, in the context of climate change. The Ecohealth approach was the main approach applied by the collaborating countries.

In 2019 TDR/WHO convened a meeting to discuss possibilities for using a One Health approach to conduct implementation research building on the experiences and outcomes of the initial collaboration referred to above. This approach entailed bridging health and environment, locally as well as globally and brings the perspective of zoonoses. The current project was therefore developed to leverage on the experiences of the MABISA project to contribute towards a One Health Scorecard introduced at the Brazzaville consultation meeting (November 2019).

This current project is located in South Africa (see Figure 3) and is being implemented in the context of KwaZulu-Natal Ecohealth Programme (KEP). It draws from lessons of the MABISA project across the 3 countries (Botswana, Zimbabwe and South Africa). The outcomes of the project will feed into the collaborative overall One Health project involving South Africa, Kenya, Tanzania and Cote d'Ivoire.

To ensure that the knowledge and resources generated during the initial TDR IDRC Research Initiative, TDR with Global Health International Group (GHGI) sought to 1) strengthen a network of Transdisciplinary Scientist-practitioners and facilitate production of a series of publications and presentations for research, education, and policy forums and 2) facilitate development of a Standardized One Health Scorecard on the basis of experiences and knowledge generated from the previous program.

As part of the network, the main goal of the South African project is to address capacity development, knowledge and learning and threat management for operationalizing One Health in South Africa.

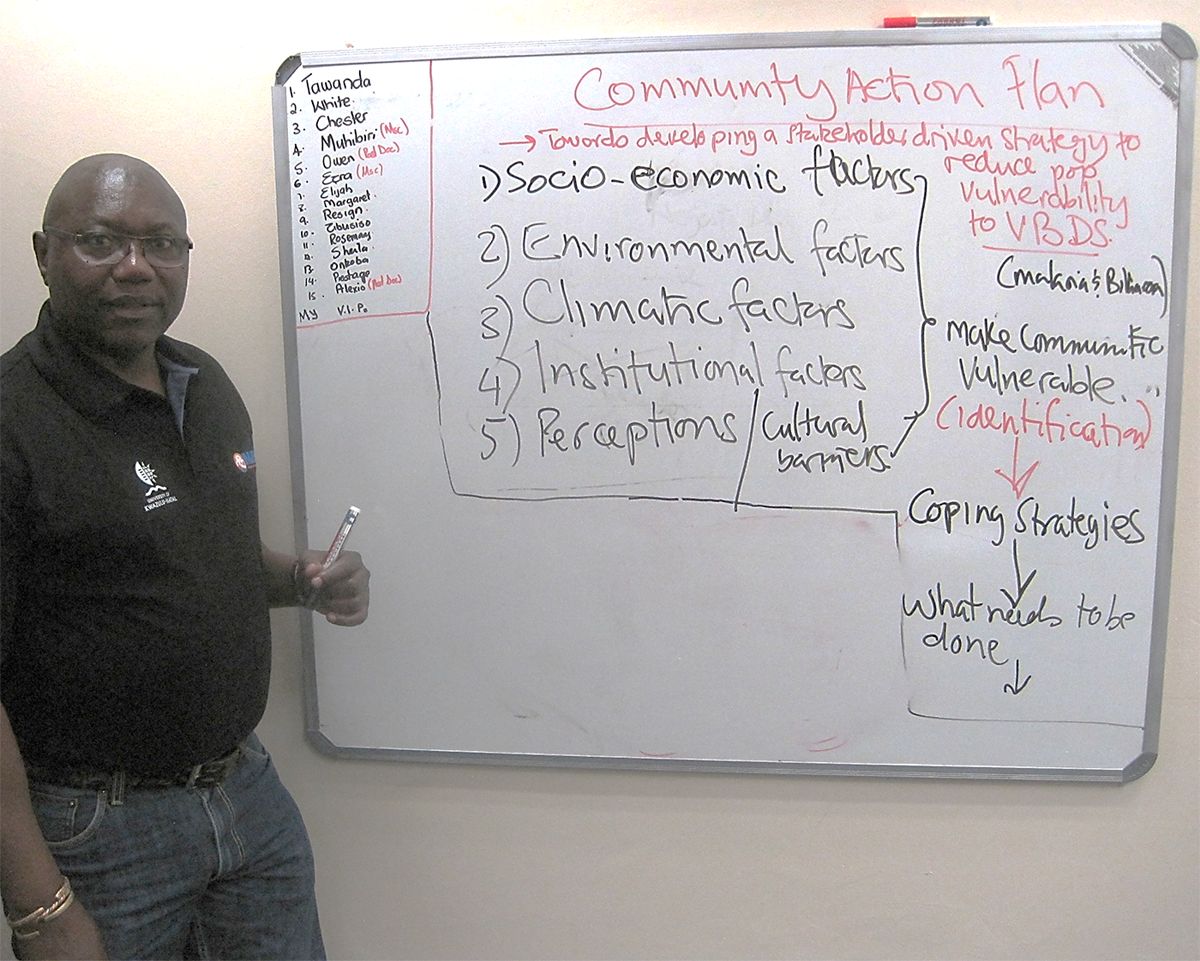

FIGURE 3. Research site in a community in South Africa

Summary of achievements:

- Local communities were capacitated to routinely collect data and promote the concept of community change makers for prevention and control of vector borne diseases including zoonosis.

- Local level structures were enhanced to facilitate co-designing of community-based projects by researchers and communities through genuine community engagement and involvement (CEI).

- Community engagement and involvement process were used to identify persisting or/and new health challenges in the study community

- An assessment of current vulnerability and resilience to VBDs in the context of shared country borders, environmental, governance, and climate change was done

Progress made towards achieving the project objectives:

Main objective: To address capacity development, knowledge, learning and threat management for operationalizing One Health in South Africa.

Specific objective 1.To enhance and develop capacity at different levels for operationalizing One Health.

The KwaZulu-Natal Ecohealth Program (KEP) has been working in Ingwavuma since 2014, when the MABISA (Malaria and Bilharzia in Southern Africa) project was initiated. Key to KEP success has been the establishment of a governance structure and operations strategy that involves the community. A 12-member Community Advisory Board (CAB) comprising of one headperson, two community leaders, three school board members, three community care givers and three ordinary community members established at the inception of the program is functional to date. KEP’s field operations were carried out by researchers and Community Research Assistants (CRAs). The presence of the CAB and CRAs had been instrumental in promoting the concept of community change makers for prevention and control of vector borne diseases including zoonosis. In addition, CRAs played a key role in data collection.

Data Collection. Over the years the KEP team had invested in equipping CRAs with both knowledge and skills to conduct research. The CRAs were trained to attain the required skills for the field work. The periodic training given to CRAs includes ethics, epidemiology of malaria and schistosomiasis, basic research methods, quality control and technical skills for data collection. The CRAs were responsible for assisting the KEP team in recruiting study participants, obtaining consent, and for data collection.

These CRAs were experienced in collecting both qualitative and quantitative data through conducting interviews, administering questionnaires, and using KoBo collect, a free open-source tool used to collect data in the field using mobile devices. CRAs also assisted in conducting focus group discussions in the local language. CRAs had also been taught how to conduct sample collection and identify vector snails and mosquito larvae. They are also knowledgeable with parasitology as they are actively involved in specimen collection and screening.

Community Change makers. KEP’s community change makers initiative was championed by teachers and primary school learners as well as CRAs. Teachers and learners, through their respective schools were involved in edutainment activities that facilitate health education in the community. Schools were engaged in an annual performance art competition where learners were actively involved in the dissemination of research results through performances. Participating schools integrated indigenous theatrical modes and everyday practices providing a rich source of familiar metaphors that aided in the construction of meaningful facilitating understanding and research uptake.

CRAs helped in developing trust between the community and the researchers, as they were familiar with the local people. Their presence allowed KEP to stay informed about the community’s perception of the project and to remain socially and culturally relevant. CRAs maintained the visibility of KEP and were the boundary partners between the research team and the community.

Specific objective 2.To co-develop a theory of change with stakeholders to easily identify priority areas for research and intervention.

This project had engaged with the various community structures and fora in an effort to co-develop a theory of change (see FIGURE 4).